Perestroika by Heather Bourbeau

“It was too late, they all said. We should start preparing, as if we had not spent the last four years sitting in the knowledge of our own mortality.”

Fiction by Heather Bourbeau

+++

My heart hurt from love and pain and anger as I held the gun two feet from your head, the head I had stroked so tenderly for twenty-two years, whose greys I had counted as they came in until the salt overtook the pepper.

We met in college, in a political economy class. I stood by Dukakis. You chose George H.W. Bush. I welcomed Gorbachev’s glasnost. You welcomed the expansion of Star Wars. I refused to shave my legs to adhere to the patriarchal demands of beauty. You refused to acknowledge the confusion my legs and breasts and smile inspired in you, until the week I fell ill and you brought my homework assignments and soup.

With friends, I would joke that I fell for the soup first, but later I would tell you how, from the first day of class, your ability to almost make me see your side with quiet kindness and misguided rhetoric piqued my mind, and the way your green t-shirt hugged your shoulders and brought out your eyes took my breath away.

Over the years, we softened. We argued politics and social injustices, made wine and hiked mountains, traveled the world, ate in the best restaurants in Moscow, rowed in hand-made canoes through jungles, learned how isolated we each grew up despite our metropolitan upbringings, and marveled at how the world was a much greyer place than we were led to believe.

We had one child, a boy who died in a car accident one gorgeous sunny day when he was 16. No drunk driver. No rain. No evil we could blame, so we wanted to blame ourselves. The two years that followed were filled with hard silences and harder embraces, spiked with heaving sobs and questions faith and family and friends could not answer.

And we survived. We came out the other end, kinder, more compassionate, quicker to laugh now that we knew how joy and life can be taken away.

We had seen the gaudy and tragic parade of death before. Cancer took my aunt, your brother, my best friend, your mother, your boss, our favorite neighbor, our niece, your friend from college, his wife, my friend’s husband, and our cat. And so when you first lost weight, we took no chances. You were scanned and screened. I signed up for therapy and support groups.

The results were negative. We sighed and shifted toward home projects and vacation plans. We made wine to be aged and got lost once again in our routine. We binge-watched “Game of Thrones” and ignored sunny days. We bickered over the wash and open drawers, and welcomed the bickering because it felt like a return to normal—a sign of healing and trust restored.

When your back began hurting, we adjusted the bed and wondered at our aging bodies. Then came the vomiting, misdiagnoses, and antibiotics, followed by confusion and then jaundice. It was the sallowing of your skin that finally convinced the doctors of what we each had felt in our bones. You were stoic and I was a wreck – or at least, that is what our friends will say, later, when they find you. In fact, I went to work, researching options, interviewing doctors, introducing art therapy and meditation into our daily routine, while you were paralyzed with fear and regret. Too much time in front of screens and not enough time loving, you yelled at me and no one. “Billy should have taught us that,” you wept into my hair. “We forgot, we forgot.” But we didn’t forget, my dear. We needed to let the scabs heal, we needed to hibernate and isolate and come back to each other and to the world.

It was too late, they all said. We should start preparing, as if we had not spent the last four years sitting in the knowledge of our own mortality. It was too late. Too late. Our friends and family and son had all died too early, and now they were telling us it was too late.

I do not know how much loss I am supposed to bear, and I am certain I will bear more before my time comes, but we would not give that little bitch cancer the satisfaction of ruining your physical beauty and seductive mind. Fate and cancer—the twin sisters of doom—had had all the power up until now. Now, you laughed, it was payback time.

My heart hurt from love and pain and anger as I held the gun two feet from your head, a head shrunken and nearly bald from the treatments, but still fantastic and striking and yours. You had said you wanted to choose the time of your death. You wanted to be in control of at least this. You would not give cancer the satisfaction of another life taken. I had suggested pills, but you wanted everyone to know this was no accident. You tried to point the gun to your head, but your muscles were no longer strong enough to hold the pistol. You shook from pain and medications, and you cried at the failure to do this one thing right, and I ached for you, for us.

I remembered the lukewarm soup and green shirt.

I remembered creating and burying our son.

I remembered marveling at your strength and softness.

And I remembered and savored how your breath first tasted upon mine. My love.

My heart hurt from love and pain and anger as I held the gun two feet from your head.

+++

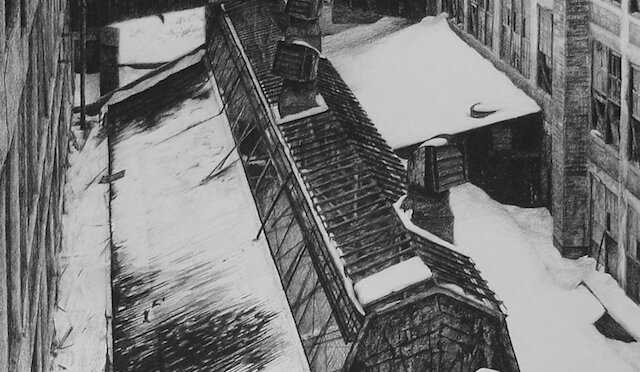

Header image courtesy of Stephanie Buer. To view her Artist Feature, go here.

Heather Bourbeau’s fiction and poetry have been published in Alaska Quarterly Review, Cleaver, Eleven Eleven, Francis Ford Coppola Winery’s Chalkboard, Nailed Magazine, The Stockholm Review of Literature, and the anthologies Nothing Short Of 100: Selected Tales from 100 Word Story and America, We Call Your Name: Poems of Resistance and Resilience (Sixteen Rivers Press). She has worked with various UN agencies, including the UN peacekeeping mission in Liberia and UNICEF Somalia.